Math for Programmers: Union and Intersection

Last week we talked about sets and how they relate to arrays. This week we will take a look at how to interact with arrays and apply two common mathematical operations on them to produce new, refined sets of data with which we can interact.

Two of the most common and well known actions we can take on sets are union and intersection. The union operation combines two sets and creates a new single set containing the elements of each of the original sets. Intersection is also a combinatorial operation, but instead of combining all elements, it simply returns a set containing the shared elements of each set.

Uniqueness

Before we can address union and intersection, we have to deal with the state of uniqueness. Last week we looked at how an array can be converted into a set by viewing each index and value as a vector. Though this is useful for seeing the relation between mathematical sets and arrays in programming, it is not quite so useful when trying to actually accomplish set operations.

The biggest issue we encounter when looking at an array is that it is more closely related to a vector in nature and behavior. If we discard the importance of array ordering, it becomes a little more set like. Let’s take a look at what this means.

// ≁ -- mathematically dissimilar

// ~ -- mathematically similar

var myVector = [1, 3, 2, 5, 7, 1, 1, 2];

myVector ≁ {1, 2, 3, 5, 7}; // This is true since a vector is ordered and requires all elements

var myArray = [1, 3, 2, 5, 7];

myArray ~ {1, 2, 3, 5, 7}; // true because our array contains only unique elements

Our second array closely matches our needs for a set, so it would be ideal to have a function which takes an array of values and returns a list with all duplicated values removed. We can annotate this function like this: (array) -> array

Although this function has been implemented in several libraries, it is easy enough to create we’ll just build it here. This not only gives us insight into how a “unique” function could be built, but it also gives us a vanilla implementation of our functionality so as we build on top of our behaviors, we know where we started and how we arrived at our current place.

function addToMap (map, value){

map[value] = true;

return map;

}

function buildSetMap (list){

return list.reduce(addToMap, {});

}

function unique (list){

return Object.getKeys(buildSetMap(list));

}

```

Now we have a clear way to take any array and create an array of unique values in linear, or O(n), time. This will become important as we move forward since we want to ensure we don't introduce too much overhead. As we introduce new functions on top of unique, it would be easy to loop over our loop and create slow functions which can be disastrous when we rely on these functions later for abstracted behavior.

Union

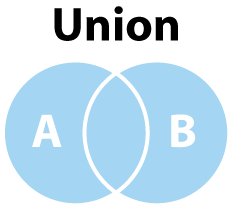

To really talk about the union operation it can be quite helpful to take a look at what a union of sets might look like. In words, union is an operation which takes two sets and creates a new set which contains all members, uniquely. This means, the union of {1, 2, 3} and {2, 3, 4} would be {1, 2, 3, 4}. Let's look at a Venn diagram to see what this means graphically.

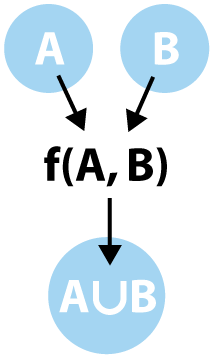

For small sets of values, it is pretty easy to perform a union of all values, but as the sets grow, it becomes much more difficult. Beyond this, since Javascript does not contain a unique function, i.e. the function we built above, nor does it contain a union function, we would have to build this behavior ourselves. This means we have to think like a mathematical operator to create our function. What we really need is a function with accepts two sets and maps them to a new set which contains the union of all elements. Using a little bit of visual mathematics, our operation looks like the following:

For small sets of values, it is pretty easy to perform a union of all values, but as the sets grow, it becomes much more difficult. Beyond this, since Javascript does not contain a unique function, i.e. the function we built above, nor does it contain a union function, we would have to build this behavior ourselves. This means we have to think like a mathematical operator to create our function. What we really need is a function with accepts two sets and maps them to a new set which contains the union of all elements. Using a little bit of visual mathematics, our operation looks like the following:

This diagram actually demonstrates one of the core ideas behind functional programming as well as giving us a goal to work toward. Ultimately, if we had a function called union which we could use to combine our sets in a predictable way, we, as application developers, would not need to concern ourselves with the inner workings. More importantly, if we understand, at a higher abstraction level, what union should be doing we will be able to digest, fairly immediately, what our function should take as arguments and what it will produce. Our union function can be annotated as (array, array) -> array. Let's look at the implementation.

```javascript

function union (lista, listb) {

return unique(lista.concat(listb));

}

```

With our unique function already constructed, this is a pretty trivial function to implement. There is, of course an item of interest here. Union is almost done for us by the concat function. Concat makes the same assumption our original exploration of converting an array to a set does: arrays are sets of vectors, so a concatenation would be an introduction of two sets of vectors into a new set, reassigning the indices in each vector to map to a new unique set.

This concatenation behavior can be quite useful, but it is not a union operation. In order to perform a proper union of the values in each array we will need to ensure all values of the returned array are actually unique. This means we need to execute a uniqueness operation on the resulting set to get our array which is similar to a set. I.e. if we have an array representing set A, [A], and an array representing set B, [B], then union([A], [B]) ~ A ⋃ B.

This diagram actually demonstrates one of the core ideas behind functional programming as well as giving us a goal to work toward. Ultimately, if we had a function called union which we could use to combine our sets in a predictable way, we, as application developers, would not need to concern ourselves with the inner workings. More importantly, if we understand, at a higher abstraction level, what union should be doing we will be able to digest, fairly immediately, what our function should take as arguments and what it will produce. Our union function can be annotated as (array, array) -> array. Let's look at the implementation.

```javascript

function union (lista, listb) {

return unique(lista.concat(listb));

}

```

With our unique function already constructed, this is a pretty trivial function to implement. There is, of course an item of interest here. Union is almost done for us by the concat function. Concat makes the same assumption our original exploration of converting an array to a set does: arrays are sets of vectors, so a concatenation would be an introduction of two sets of vectors into a new set, reassigning the indices in each vector to map to a new unique set.

This concatenation behavior can be quite useful, but it is not a union operation. In order to perform a proper union of the values in each array we will need to ensure all values of the returned array are actually unique. This means we need to execute a uniqueness operation on the resulting set to get our array which is similar to a set. I.e. if we have an array representing set A, [A], and an array representing set B, [B], then union([A], [B]) ~ A ⋃ B.

Intersection

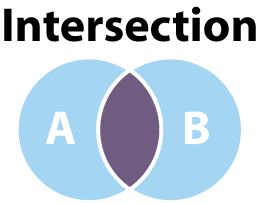

Much like the union operation, before we try to talk too deeply about the intersection operation, it would be helpful to get a high-level understanding of what intersection means. Intersection is an operation which takes two sets and creates a new set which contains only the shared elements of the original sets. This means the intersection of {1, 2, 3} and {3, 4, 5} is {3}. Visually, intersection looks like the following diagram.

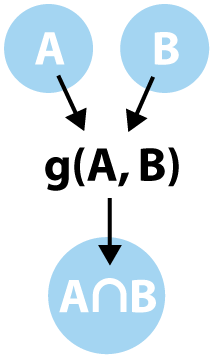

The darker region represents the intersection of sets A and B, which, from our first example, is a set containing only the value 3, or {3}. Much like the union operation, we can create a function intersect which takes two sets and returns a new set containing the intersection. We can diagram this in the same way we did with union.

The darker region represents the intersection of sets A and B, which, from our first example, is a set containing only the value 3, or {3}. Much like the union operation, we can create a function intersect which takes two sets and returns a new set containing the intersection. We can diagram this in the same way we did with union.

This diagram shows us the close relation between intersect and union functions. The annotation for our intersection function is, actually, identical to our union function: (array, array) -> array. This means they share the same contract and could be used on the same sets to produce a result which, incidentally, will match the contract for any function which takes a set of values as a list. Let's have a look at what the implementation of intersect looks like in Javascript.

```javascript

function addIfIntersect (map, accumulator, value){

return map[value] ? accumulator.concat([value]) : accumulator;

}

function intersect (lista, listb){

var mapb = buildSetMap(listb);

return unique(lista).reduce(addIfIntersect.bind(null, mapb), []);

}

```

As expected, the difference between union and intersection is in the details. Where union performed the combination before we performed a unique operation, intersections can only be taken if all of the values are already unique, This means intersections are slightly more computationally complex than a union, however, in the large, intersection is still a linear operation. We know this by performing the following analysis:

This diagram shows us the close relation between intersect and union functions. The annotation for our intersection function is, actually, identical to our union function: (array, array) -> array. This means they share the same contract and could be used on the same sets to produce a result which, incidentally, will match the contract for any function which takes a set of values as a list. Let's have a look at what the implementation of intersect looks like in Javascript.

```javascript

function addIfIntersect (map, accumulator, value){

return map[value] ? accumulator.concat([value]) : accumulator;

}

function intersect (lista, listb){

var mapb = buildSetMap(listb);

return unique(lista).reduce(addIfIntersect.bind(null, mapb), []);

}

```

As expected, the difference between union and intersection is in the details. Where union performed the combination before we performed a unique operation, intersections can only be taken if all of the values are already unique, This means intersections are slightly more computationally complex than a union, however, in the large, intersection is still a linear operation. We know this by performing the following analysis:

- unique is O(n) as defined before

- reduce is O(n) by the nature of reduction of a list

- buildSetMap is also O(n) as it was the defining characteristic of unique.

- intersect is the sum of three O(n) operations, or intersection performs 3n operations, making it, also, O(n)

This algorithmic analysis is helpful in understanding the general characteristic of a function and how it will impact execution time in a larger system. Since union and intersect are both O(n) functions, we can easily use them in a chained way, resulting in a new O(n) function. What this also tells us is, union and intersection are sufficiently performant for small sets of data and acceptable for medium sets. If our sets get large enough we might have to start looking at ways to reduce the number of computations needed to complete the process, but that's another blog post.

Summary

We can actually use our union and intersect functions together to quickly perform complex mathematical behavior on even non-optimal arrays. Since these functions perform normalization on our sets of data, we can use rather poorly defined arrays and still get meaningful results. Let's take a quick look at a small example where we set A, B and C as poorly defined arrays and then perform A ⋃ B ⋂ C.

```javascript

var A = [1, 2, 4, 3, 7, 7, 8, 3],

B = [5, 4, 7, 9, 4, 10],

C = [1, 2, 3, 2, 4];

intersect(union(A, B), C); // [1, 2, 3, 4]

```

In this post we discussed performing union and intersection operations on arrays of data, as well as implementations for each and their performance characteristics. By understanding these core ideas, it becomes easier to understand how data can be quickly and descriptively modified programmatically. This core understanding is useful both for working with arrays inside of your application as well as better understanding the way data is interrelated in database considerations. Now, go munge data and make it work better for you!