Anticipating User Falloff

As we discussed last week, users have a predictable tolerance for wait times through waiting for page loading and information seeking behaviors. The value you get when you calculate expected user tolerance can be useful by itself, but it would be better if you could actually predict the rough numbers of users who will fall off early and late in the wait/seek process.

It is reasonable to say that no two people have the same patience for waiting and searching. Some people will wait and search for an extraordinary amount of time while others get frustrated quickly and give up almost immediately. To expect that all of your users will hold out until the very last moment of the predicted 13, or so, seconds hardly reflects reality.

Instead, we can say that we have some maximum tolerance, L, which we can compute which the very last holdouts will actually wait for. Unfortunately, we also know that a majority of users, if they have to wait very long, won’t even see your site since they will fall off before the page finishes loading. This means that the bulk of the users which see your site will be something less than the number of users who actually attempted to load your site.

There were some really smart guys who lived about 100-200 years ago and did lots of math. The really neat thing is they did a lot of work that I don’t have to reproduce or prove since they were smarter, more patient and far more talented than I am. One of them was named Carl Friedrich Gauss, who some refer to as the Prince of Mathematics. He was really smart. Newton smart. Possibly smarter than Newton.

What does Gauss have to do with user experience?

Gauss is the guy who figured out how to evaluate (1/(2pi)^.5)e^(-1/2*x^2) when integrated from negative to positive infinity. Did I just see your eyes glaze over? It’s alright. That happens to me a lot.

What this really translates to is, Gauss figured out how to work with the statistical standard normal curve. This probably means a lot more to you, right? This function happens to be really useful in developing something meaningful regarding users and their falloff over time from initial click through to our tolerance, L.

I spent an entire weekend where I slept little and did math a lot. During that time, I developed a function, based on the standard normal curve which says something reasonably meaningful about users and how long they are willing to stay on your site and either a) search for what they need and b) not satisfice. I’ll give you the function without justification. Contact me if you want all the formalities, I have them in a folder, on the ready.

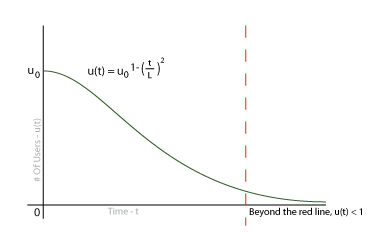

Our function looks something very much like the following:

u(t) = u_0^(1-(t/L)^2)

What this says is that the number of users still on your site, at time t, is equal to the initial users times some falloff function evaluated for t. The cool thing is, we already know everything that goes into this little gem when we are testing. We know how many users we started with and we know what L is. The really interesting bit is, when t>L, u(t) is less than one. This means that the probability we will have a user after we reach the maximum tolerance is exactly what we expect it to be.

Below is an estimation of what the graph would look like for your analysis:

[caption id=”” align=”alignnone” width=”380” caption=”User Falloff Over Time”] [/caption]

[/caption]

This may not seem like much of a revelation. We all know that, as people run out of patience, they leave the site. What this does is it gives us something we can plug into our calculators and project some sort of quantified result. What this also means is, if you can produce results which fall beyond the bounds of this graph as you are testing, you know you are outperforming expected results. You can also use this to compare to the number of people who satisfice during testing.

Probably one of the most important things is comparing the number of users who remain on a site for an expected amount of time to the amount of time needed to produce a conversion. This offers a real, concrete means to offer up ROI on your efforts to encourage users to remain on your site.

The uses of this modest function are so numerous I can’t afford the space here to list them. I will offer up more insight into this function as well as other, related, functions which can be used for further prediction. I encourage you to sit and play with this. See how it compares with your test findings. Gauge how you are performing against the model. Improve and test again and, above all else, make the web a better place.

User Frustration Tolerance on the Web

I have been working for quite a while to devise a method for assessing web sites and the ability to provide two things. First, I want to assess the ability for a user to perform an action they want to perform. Second I want to assess the ability for the user to complete a business goal while completing their own goals.

Before we start down this particular rabbit hole, there’s a bit of a prerequisite for our discussion. It is important that you understand Fitts’ Law and its generalization, the Steering Law. These are critical to understanding how much time a user will be willing to dedicate to your site the first time they arrive, or after a major overhaul, before abandoning their goals and leaving the site.

So, let’s suppose you have users visiting your site, or, better yet, you are performing user testing and want to evaluate how your site is performing with the users you are testing. It is important to have a realistic expectation regarding what users would really tolerate on the web before they leave so you can evaluate the results of your test accordingly.

Most users have some sort of tolerance level. By this, I mean most users are only willing to give you a fraction of their day before they get fed up. Reasonably, some users will have a shorter fuse than others, but all will eventually blow the proverbial gasket and leave your site, never to return. Let’s call this tolerance for pain and frustration ‘L.’

L is the amount of time, typically in seconds, that your user is willing to spend time looking over your site and trying to accomplish their goals. It is becoming common to say that a user will attempt to satisfy a goal and, ultimately, they will attempt to satisfice if nothing else seems to work.

When they hit the satisfice point they are reaching their tolerance for frustration. The satisfice action comes quickly, so we have very little time to fully satisfy the user. There are actually 3 items which go into the base tolerance before satisficing occurs:

- The maximum acceptable page load time (p)

- The maximum time it takes after page load to locate a satisfactory action to achieve their goal (g)

- The Fitts'/Steering time it takes to get to their preferred action item (fs)

The maximum acceptable page load time seems to range from one to ten seconds depending on who you talk to or read on the web. I am opting to take the average and say that the maximum page load time should take around five seconds, though this can vary depending on other factors which are outside the scope of this discussion.

Users, once the site has loaded, have a maximum time they will spend searching for something to satisfy their goals. The number I keep seeing thrown around is seven seconds, so I am going to accept that as my number for a general baseline for user behavior.

Finally we have Fitts’ Law and the Steering Law. This lends a little complication to the matter as these functions will return varying results. The simplest case would be a Fitts’ law case where the user can move directly to an item on the screen without interruption or interference. Each person knows how much time it takes them to move from one place to another on the screen and they will, generally, allow for time to move the cursor to a target.

If the screen does other, unexpected things while the user is moving their pointer, like opening and closing ads, displaying inline pop-ups which cover the target or other interferences, the user will get distracted and frustrated. This is where a Fitts’ Law asset can become a Steering Law liability. A frustrated user is far more likely to leave than a satisfied user. For each item which interferes with the user’s ability to move to their target, their patience will wane. Reasonably, then, using the variables I defined above, we can calculate the tolerance constant as follows:

L = p + g + fs - (sum of all subsequent change in fs)

Better yet, if we plug in the basic values I collected from around the web, we get this:

L = 5 + 7 + fs - (sum of all subsequent change in fs) = 12 + fs - (sum of all subsequent change in fs)

Moving from one place on the screen to another is a relatively quick motion, so we can see, given there aren’t major issues with user-flow interruption, that the average user tolerance is going to be between 12 and 13 seconds for a site from beginning to end. That’s not a very long time, but to a user, it’s an eternity. Don’t believe me? Sit and watch the clock for 13 seconds, uninterrupted. Go on, I’ll wait.

Kind of a painful experience, isn’t it? Keep this in mind as you create your site and watch users test it. During your next test, run a stopwatch. If it takes your tester more than a quarter of a minute to sort everything out and do what they were tasked with, you have some serious issues to consider.

I threw a lot out in one little post, today. Let it soak for a while and tell me what you think in the comments. As you work on guiding users through your site and as you test, think about the 13 seconds just watching the clock tick. Consider your user and their tolerance for frustration and pain. Keep the journey quick and painless and make the web a better place.

Google Geocoding with CakePHP

Google has some pretty neat toys for developers and CakePHP is a pretty friendly framework to quickly build applications on which is well supported. That said, when I went looking for a Google geocoding component, I was a little surprised to discover that nobody had created one to do the hand-shakey business between a CakePHP application and Google.

That is, I didn’t find anyone, though they may well be out there.

I did find several references to a Google Maps helper, but, that didn’t help too much since I had an address and no geodata. The helpers I found looked, well… helpful once you had the correct data, mind you. Before you can do all of the maps-type stuff, you have collect the geodata and that’s where I came in.

I built a quick little script which takes an address and returns geodata. It isn’t a ton of code, it doesn’t handle paid accounts and it isn’t fancy. What it lacks in bells and whistles, it makes up for in pure, unadulterated Google Maps API query ability. Let’s have a look at how to implement the code.

First, download the file and unzip it. Place it in /app/controllers/components. That’s the bulk of the work. Once you have the component added to your components directory, just add it to the components array in your controller and call the getCoords() function like in the code below.

class FakeController extends AppController

{

var $components = array("Googlegeocode");

/* functions and whatever other code ... */

function getGeoData()

{

$address = $this->data["ModelName"]["address"];

$coords = NULL;

if($address)

{

$coords = $this->Googlegeocode->getCoords($address);

}

$this->set("coords", $coords);

} // End of function

} // End of class

```

There is more code there in general class setup and comments than there is in actually making the coordinate request. Note, do not URL encode your address before passing it into the function. This can have unexpected results as the geocoding component will properly encode the address for you.

There are a couple of other functions in case you need them. First is a call to retrieve the data set which is returned from Google.

// ... code ...

$geodataRecord =

$this->Googlegeocode->getGeodataRecord($address);

// ... code ...

```

This will return an array built directly from the XML returned by Google. From this you can extract all of the information they typically return, including status, address information and geodata as well as several other odds and ends. There is actually quite a bit of data returned for each address.

Two other useful functions are the lastCoords() and lastGeodataRecord() functions. They are called as follows:

// ... code ...

$coords = $this->Googlegeodata->lastCoords();

$geodataRecord = $this->Googlegeodata->lastGeodataRecord();

// ... code ...

```

Once a record is retrieved, it is stored in memory until a new record is requested. You can refer to these as needed to recall the latest records retrieved from Google until the script finishes executing.

Though this isn't the typical user experience related post, hopefully this will help you get moving more quickly on your project involving geocoding addresses for use with the Google Maps UI API. I hope you find my component useful and you use it to make the web a better place.

Small Inconveniences Matter

Last night I was working on integrating oAuth consumers into Noisophile. This is the first time I had done something like this so I was reading all of the material I could to get the best idea for what I was about to do. I came across a blog post about oAuth and one particular way of managing the information passed back from Twitter and the like.

This person will remain unidentified as I don’t want gobs of people spamming his site, nor do I want to give his poor judgement any extra exposure. That said, the basis of the post was, it is preferable to make users authenticate with Twitter every time they logged into the system as opposed to storing the keys and remembering who the users of the site are.

The take-away message was, paraphrased, “it’s a simple back and forth between your site and Twitter each time they log in. It won’t bother the user and it is preferable to storing all of those authentication keys.”

Let me say it again: he was evangelizing inconveniencing the user and stating this was actually the preferable thing to do.

This idea is wrong-headed in so many ways. First, let’s look at Twitter and see how they would feel about it, shall we?

Suppose we stored the keys for the user. Twitter would have to generate a key just once for each user. Once that work was done, they would simply take requests as usual and the day would go on. Their API is built around using stored user authentication so this is no extra burden. Instead it is business as usual.

Now, suppose you make your user re-authorize every time they signed in to your web app. This means that each user would have to hit the Twitter authorization page once per login. Now Twitter has to burn the extra cycles to generate a new key for YOUR user. On top of that, there is storage of that key. Each time you request a key, you are taking up space on their server.

The more times you make your users request authentication, the more it costs Twitter. It might be no big deal to you, but that is money out of THEIR pocket. That is the very same pocket which is financing that lovely API you are using to update your user’s timeline. We haven’t even started talking about your users yet. This is just the mess for Twitter.

Let’s have a look at your user. If you store their authentication, they have to hit the Twitter authentication screen just once. Once they do that, they will probably forget all about it, carrying on with using your application, like they want to. That’s it.

Suppose you, on the other hand, make your user authenticate every time they log in. One of two things is going to happen. Either you make them authenticate through an account screen and they will assume, after the first time, that they are done. The other option is, as soon as your user logs in, they will be faced with a Twitter authentication screen.

Suppose you make them authenticate through an account screen. Your user will reasonably assume this was a one-time thing. Later they will discover that Twitter isn’t being updated by your app anymore. They will check their account and see they have to re-authenticate.

Rinse, repeat.

Eventually, your user will figure out that you expect them to re-authenticate EVERY time they log in. If your application relies heavily on Twitter updates, you will lose that user. If that user liked your application because it updated twitter, you will lose that user. In the end, you are likely to lose users over the choice.

Suppose you force your user to re-authenticate each time they logged in. Your users are going to view logging in to your service as a chore. Eventually they will tire of the whole process and leave. This is the most direct route to losing users.

Regardless of the path you take, you are bound to lose users if you make them re-authenticate through a service each time they log into your service. Also, the more services your app interacts with, the more services your user will have to re-authenticate each time they log into your app. This compounding effect will only drive users away faster.

In the end, what this person was really evangelizing is simply laziness. It is unreasonable to expect your user to go through a litany of special operations each time they log in before they can fully use your service. In this day of “less is more” user interaction, asking the user to perform unnecessary actions is a sure-fire way to drive users from your site and fast. Think about your user. Do a little work for them and make the web a better place.

Know Thy Customer

I’ve been tasked with an interesting problem: encourage the Creative department to migrate away from their current project tracking tool and into Jira. For those of you unfamiliar with Jira, it is a bug tracking tool with a bunch of toys and goodies built in to help keep track of everything from hours to subversion check-in number. From a developer’s point of view, there are more neat things than you could shake a stick at. From an outsider’s perspective, it is a big, complicated and confusing system with more secrets and challenges than one could ever imagine.

Years ago, I built a project tracking system for the Creative department at my current company which they use for everything. More projects come and go through the Creative project queue than I had planned on, but it has held together reasonably well. That said, the Engineering director would like to get everyone in the company on the same set of software in order to streamline maintenance efforts.

In theory, this unification makes lots of good sense. Less money will be spent maintaining disparate software and more will be spent on keeping things tidy, making for a smooth experience for all involved.

Unsurprisingly, I was met with resistance from the Director of Communications. She told me she was concerned about the glut of features and functions she had no use for. She prefers the simple system because the creative team is a small team of three. Tracking all of the projects a small team has is just challenging enough to require a small system, but not so challenging that she needed all the heavyweight tools a team of 50-100 people would.

I am currently acting as negotiator between the Engineering and Creative departments. Proposals and counter proposals are being thrown back and forth and I’m caught in the middle. The challenge I see sneaking about in the grass is that the Engineering team doesn’t know their customer.

This doesn’t mean the Engineering team is bad. It doesn’t mean they don’t care. It simply means they don’t live in the same headspace the Creative team does and they don’t have enough time to think about it.

This puts me in a sticky situation.

I worked exclusively with the Creative team for the first two years I was with the company. I ate lunch with them, worked with them, met their deadlines, played by their rules and build 95% of the tools they use today. It was a really great insight into what a creative time is really like. Something many engineers never have the opportunity to experience.

Now, I am part of the Engineering team again and playing by their rules. Engineers think differently. I am an engineer and my father was an engineer before me. I know a thing or two about engineers and their quirks. Ultimately, I can see both sides of the argument and the standoff is looking a little hairy.

“So, where are you going with all this,” you might ask.

If you are going to propose a solution to a problem, instead of learning all you can about the solution you are going to offer, learn about your customer instead. Don’t try to shoehorn a customer into a solution saying “it kind of does most of what you need as long as you need the stuff it does.” It will never work out for you.

Learn your customer’s language. Uncover little secrets about them and figure out how they really work. Customers will rarely pony up and say “here’s everything you need to know about us and our problem.” Almost always, they say “here is our problem. Fix it.”

If you don’t know your customer, you’ll never solve their problem. If, on the other hand, you DO know your customer, you have a fighting chance. Mind you, even if you know your customer, they may still disregard your solution anyway, but at least you know you gave them the best you had.

Don’t fret if it takes some time to learn to think like your customers, though. It’s not something that comes overnight. I know it took a while for me to stop thinking like an engineer for 30 seconds and think like a designer. One day, I woke up and everything had to be diagrammed. There were so many things which could only be said through images. The shift happened and the code disappeared.

Look for the transparency. If you can stop and step into your customer’s head for a few minutes you may discover that the real problem is not the issue they have with the solution you offered, it may be with the solution that doesn’t solve their problem. Creatives, engineers, accountants, executives and marketing people all work in different ways. Businesses are much the same. Find how their problem is different and you will find the solution. Know thy customer and make the web a better place.